2020 was a bad year for China’s Belt and Road Initiative

3 min read

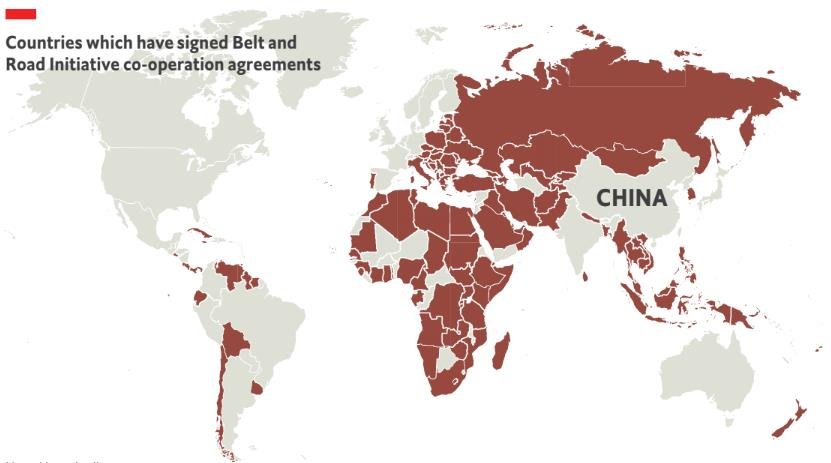

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has become an extension of the Chinese economic nervous system growing out of the Middle Kingdom. Infrastructure projects ranging from railroads in Southeast Asia to ports in Oman have defined the strategy of the new Silk Road. The BRI has become the highlight in Beijing’s diplomacy as it makes friends with the Taliban and attempts to balance the hostility between Iran and Saudi Arabia to ensure the success of its generational project.

Though it brands itself as having grand ambitions and bringing economic development to areas that have struggled to adapt to modernity, the BRI has been the target of fierce criticism from many western governments.

The term “debt-trap diplomacy” was coined in 2017 to describe what many critics see as Chinese neocolonialism being veiled by the BRI. That’s because, when these countries fail to pay back these loans, Beijing takes control of a part of that country’s assets. Sri Lanka, which borrowed heavily from China to build a new port, had to forfeit that port to China when they could not afford to pay for it.

Despite the early success, the BRI came to a sudden halt last year as COVID-19 ravaged the globe. Progress on the new Silk Road has slowly resumed, but the economic consequences of the virus are still shaking many of the nations that China has partnered with to expand the BRI. Now, many of those nations are asking China to reduce or forgive those loans – which could have consequences for the rest of the world.

Officials at the World Bank believe the global economy contracted by at least 5% last year as it entered the worst recession since the Second World War. The countries most affected by the pandemic are those most reliant on global trade, commodity exports and external financing – nations that are typically part of the BRI.

Because of the disproportionate effect the pandemic had on these nations, many will find it even more difficult to repay loans from China. Last November, Zambia became the first nation to default when the southern African nation failed to repay its US$12 billion debt.

More than 10 nations entered debt negotiations with China in 2020, including Pakistan, which is the largest recipient of Chinese investment. Other nations include Ecuador, Venezuela, Laos, Tanzania, Togo, Laos, Mozambique and Kyrgyzstan.

Ukraine, the Maldives and Djibouti have renegotiated debt in previous years.

The World Bank found that one-third of all participating BRI nations have systematic economic weaknesses that could prevent them from repaying their loans. This may be why the BRI was beginning to slow even before the COVID-19 pandemic undercut the global economy.

An estimated US$12.6 billion in projects was canceled by the end of 2019 and another US$20 billion and US$64 billion have been delayed or paused. The pandemic worsened an already declining situation. Even the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs admitted that one-fifth of BRI projects have been “seriously affected” by the pandemic.

Corruption is another possible weakness to the BRI. Maldivian Finance Minister Ibrahim Ameer has claimed that members of a previous Maldivian government got kickbacks from contractors, raising the cost of the projects. Critics of the BRI may argue that while Beijing is not responsible for corruption in BRI partners, it is a marriage of convenience for China.

However, despite many nations included in the BRI being poor and corrupt, there are exceptions.

New Zealand is a member of the BRI, which has complicated the geopolitical situation in the South Pacific as relations between Australia and China continue to deteriorate. Oman is also a partner and its efforts to transform the small fishing village of Duqm into a global center for maritime trade appears to be going well.

But New Zealand and Oman are not the typical nations that receive heavy BRI investment. Most are like Zambia, which began debt renegotiations with China in 2017, years before COVID-19 was a household term.

Many of these nations are aware of their weaknesses and with a global recession still hampering markets, demand for loans is declining and the future of the BRI remains uncertain.

(Originally Pubslished on The Millennial Source)