Political economic instability and Wang Yi’s peripheral diplomacy in Sri Lanka

7 min read

By Asanga Abeyagoonasekera

To ease the pressure from Beijing, the day before the Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Sri Lanka, US $6.9 million was paid to Qingdao Seawin Biotech Group. A few months ago, the Chinese fertiliser company had blacklisted the local Sri Lankan bank. Colombo’s neutralising effort reduced the Chinese pressure, especially from Wang Yi’s bilateral agenda. During the Foreign Minister’s visit, Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa requested that “it would be a great relief to the country if attention could be paid on restructuring the debt repayments as a solution to the economic crisis”, which will give Beijing an ample and comfortable space to expand its sphere of influence on the island.

Wang Yi visited the Colombo Port city, a large-scale infrastructure project that is a part of the Belt and Road Initiative.

An economic crisis overshadowed the unseen strategic implications of such moves. Sri Lanka has to repay US $4.5 billion in debt in 2022; the ailing economy with plummeted foreign exchange is facing a worsening economic crisis day by day. To ease the economic crisis and the emerging island-wide power cuts, Sri Lanka’s Finance Minister Basil Rajapaksa requested assistance from India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar through a credit facility of US $1.5 billion. Chinese loans account for more than US $5 billion, which was invested in infrastructure; unfortunately, it failed to produce the expected revenue, through no fault of the lenders. A range of issues ranging from domestic corruption, investment in non-productive projects along with high debt-servicing costs have caused this burden. Wang Yi visited the Colombo Port city, a large-scale infrastructure project that is a part of the Belt and Road Initiative. At present, there is limited foreign investment and foreign investors have shown little interest, though the Port City Managing Director Houliang Jiang had stated to this author during an interview in 2019 that “there will be international investors, especially from India and many other nations”. However, little progress has been made on that front.

Achieving the Chinese project goals to support the ailing Sri Lankan economy will be a daunting challenge, especially under present political conditions and Rajapaksa’s foreign policy posture, which is to hedge between New Delhi and Beijing. Three weeks prior to the Chinese foreign minister’s visit, the Chinese Ambassador Qi Zhenhong’s visit to the northern province was approved by Colombo. Sri Lanka’s hedging foreign policy in the context of alignment strategy, forging protective ties with India and China simultaneously, is clearly visible. Welcoming Chinese assistance to the Northern Tamil community, while an all-out support articulated to India by ‘India first’ posture is an example of Colombo’s hedging exercise. Some analysts who assess that smaller states play both countries against each other in the hope of finding more sustainable investments and to get some respite from further debt-trap diplomacy, have missed China’s stealth security dimension. China has indicated its interest in developing the Northern province, the closest geography to India’s immediate periphery from the south.

Welcoming Chinese assistance to the Northern Tamil community, while an all-out support articulated to India by ‘India first’ posture is an example of Colombo’s hedging exercise.

South Indian geography directly influences Sri Lanka’s north. New Delhi has voiced Tamil grievances, including a political solution since the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord in 1987. At present, for the first time, China has strategised a dual approach to satisfy the majority Sinhalese and minority Tamil community at the same time. The Chinese Ambassador’s visit and the substantial assistance from China to the Northern Province is a strategic move to expand the Chinese footprint, by initially targeting an important stakeholder stressed by South India, the fisheries community.

Beijing’s strategic circle orchestrated the Ambassador’s visit. It was not something the Chinese embassy in Colombo could decide alone due to the highly sensitive nature of the initiative. Carrying out Hindu rituals at a famous temple, inspecting northern waters with the Sri Lankan navy, and stating “this is just the beginning” are scripted exercises by Beijing aimed at sending a signal to New Delhi. The timing of this visit was well calculated. This came days after Finance Minister Basil Rajapaksa cemented the bilateral economic assistance in New Delhi, and the Chinese contaminated fertiliser consignment was rejected, where India filled the gap, followed by the Chinese renewable energy project in the three northern islands being rejected;, this trifecta is what pushed Beijing to look for an alternative strategy to reduce the growing Indian influence in Sri Lanka. By cancelling the Chinese renewable energy project in the northern islands due to India’s security concerns, Colombo kept nudging Beijing that it was beyond its control. India has not given significant attention to its South due to its passive foreign policy posture. Unfortunately, the ground reality in the present context has changed, and India needs to understand the significant security threat to its immediate marine periphery. The visit of the Chinese Ambassador to the North is a signal to both Sri Lanka and India that China is ready to take the extra risk of reaching out to the Tamil geography and intervening in India’s southern sphere. Beijing has read New Delhi and Colombo well, and it knows the limits of India and Sri Lanka and the post consequences of the Ambassador’s visit.

By cancelling the Chinese renewable energy project in the northern islands due to India’s security concerns, Colombo kept nudging Beijing that it was beyond its control.

Usually, China maintains that it will ‘not comment’ on Sri Lanka’s internal affairs. It did not support the UNHRC process to address the human rights concerns of the Tamil community in Sri Lanka. The Chinese Ambassador’s visit is also an early warning that China could use an alternative strategy to depart from supporting the Rajapaksas at the UNHRC and not use the veto against the Tamil community; it’s also a direct message to India that China is ready to voice and support the Tamil community. The Chinese manoeuvring space in Colombo has become easier with a regime tied to the Chinese ‘strategic trap’, supported by the Rajapaksas who are not ready to approach the International Monetary Fund for economic assistance. Dr Ganeshan Wignaraja observes, “China can usefully add its powerful voice to calls for Sri Lanka to seek IMF assistance”, rather China has chosen to take advantage of the semi-autocratic political environment in Sri Lanka to promote an alternative model to the democratic model and expand its economic assistance.

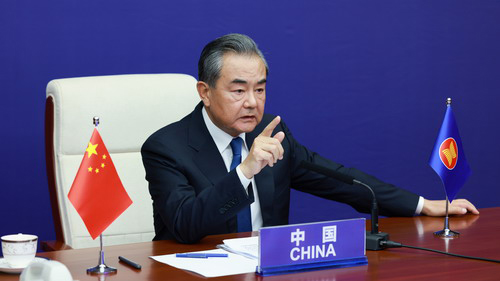

In this high-intensity environment, the Chinese Foreign Minister’s visit to Colombo is a clear sign of China projecting its grip and reassuring the Rajapaksas’ commitment towards China. The Chinese Foreign Minister visited four other nations before coming to Sri Lanka including Eritrea, Kenya, Comoros, Maldives, all of which have debt crises that are slowly converting into ‘strategic traps’. Wang Yi, known as the ‘Silver Fox’ in Chinese diplomacy, has ample experience in peripheral diplomacy in China’s vicinity to consolidate regional hegemony, a strategy advanced to fulfil President Xi’s vision to create a ‘Community of Common Destiny’. Wang Yi is now exercising peripheral diplomacy in India’s vicinity. The recent design of a new forum for Indian Ocean Island nations is a counter grouping strategy against India’s existing Indian Ocean littoral network, impacting India’s periphery. Beijing has calculated its strategy by selecting Sri Lanka as a perfect launchpad to pitch the idea, given Sri Lanka’s geography and the Rajapaksa regime’s clear China preference. Calculating this macro geopolitical viewpoint is an essential ingredient for Colombo’s foreign policy; unfortunately, it is misread most of the time. Trilateral India, Maldives, and Sri Lanka security dialogue held in early December are important initiatives but inadequate to address a rising power in India’s vicinity. The dynamics of the relationship between India-China and China-Sri Lanka have entirely changed in recent times—China spends four times as much on defence than India and China’s GDP is more than five times that of India. India would need a more active foreign policy, expanding the strategic dimension in its outreach to blunt Chinese presence in its immediate periphery.

Beijing has calculated its strategy by selecting Sri Lanka as a perfect launchpad to pitch the idea, given Sri Lanka’s geography and the Rajapaksa regime’s clear China preference.

While foreign policy course correction is required, internal cracks emerge in Rajapaksa’s political circle. The ousted minister with decades of experience in legislature and judiciary warned that the ‘the internal weak policy decisions with the absence of an inclusive approach for constitution-making, departure from democratic norms, and a weak foreign policy will invite a significant threat to nation’s sovereignty’. President Gotabaya exposed his heavy autocratic rule to the inner circle of senior ministers, which will directly concern the Prime Minister who has engaged in politics for decades with his senior political peers. The cracks will run deep and spread throughout the regime’s core in the months to come due to the aggressive style of autocratic rule. The internal political dysfunctionality was further explained by former President Maithripala Sirisena, signalling a possible departure of Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) from the coalition government. While domestic politics will take centre stage in the coming months, the underlying critical foreign policy concerns should also be prioritised. Colombo should see the larger geopolitical context and invest more in the right partnerships to push back against hostile foreign influences and sustain a balance in its foreign policy.

(Asanga Abeyagoonasekera is an international security and geopolitics analyst and strategic advisor from Sri Lanka. He has led two government think tanks providing strategic advocacy. With almost two decades of experience in the government sector in advisory positions to working at foreign policy and defence think tanks, he was the founding Director-General of the National Security Think Tank under the Ministry of Defence (INSSSL) until January 2020. Earlier, he served as Executive Director at Kadirgamar Institute )